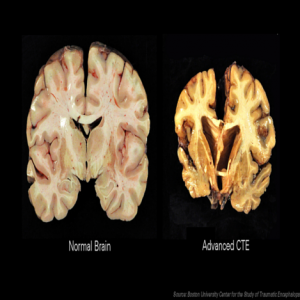

Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) is a degenerative brain disease diagnosed in an increasing number of ex-NFL football players. It’s linked to depression and dementia. There is no cure.

Until now, CTE has only been diagnosed in post-mortem autopsies. A diagnosis is made when an examination of the brain reveals a buildup of an abnormal protein called tau. Tau strangles brain cells in areas that control memory, emotions and other functions.

But ESPN reports that an expert research team has come up with new brain scan technology that can diagnose CTE in living patients.

The technology relies on a radioactive marker to identify tau in the brain. So far, testing has been performed on eight former NFL players, including Hall of Famers Tony Dorsett and Joe DeLamielleure, and All-Pro Leonard Marshall. All three have been diagnosed with signs of CTE.

Neurosurgeon Julian Bailes acknowledges that the sample size is small and testing is in its early stages. But preliminary data seems very strong, reports Bailes. He says the scans reveal tau buildups in areas of the brain that correlate exactly to their findings in autopsy exams.

DeLamielleure said he was never officially diagnosed with a concussion throughout his 13-year career as an offensive lineman. But after thousands of blows to the head, he thinks his concussion count is somewhere around 100.

“I can guarantee you my CTE, my tau, came from hits, came from blows to the head,” says DeLamielleure. He suffers from anxiety and chronic insomnia and admits to dealing with mood swings and thoughts of suicide.

Former Cowboys running back Tony Dorsett faces memory loss and depression. He says he couldn’t remember where he was going after boarding a plane that would take him to the CTE research facility at UCLA. Such memory lapses are commonplace for Dorsett.

Dr. Robert Cantu, a senior advisor to the NFL’s Head, Neck and Spine Committee, believes the new testing could be the “the holy grail in CTE diagnostics…It’s exactly what [researchers] need.”

The hope is that diagnosing CTE in living patients will lead to treatment for the disease.

Researchers are optimistic. “Until we had the ability to see it in a living, breathing person, we had no chance of helping them,” said Bailles. “It gives us the ability to track it, to see if it gets worse, or hopefully, maybe it gets better with medication, with intervention, with new discoveries.”

The findings give hope to those suffering from CTE. “I’m trying to slow this down or cut it off,” says Tony Dorsett. “I’m hoping that I’ve got another good 30 years or so.”